“I’m stubborn,” he says. “That’s probably how my friends would describe me.”

That stubbornness showed up early. Growing up in Modesto, California in the 80s and 90s meant long days outside, skateboarding until dark, getting into trouble, and doing it all again the next day. Skateboarding wasn’t a phase. It was a commitment.

“You’d wake up, meet your friends, and skate all day. As soon as school was over, you were skating. It was an obsession.”

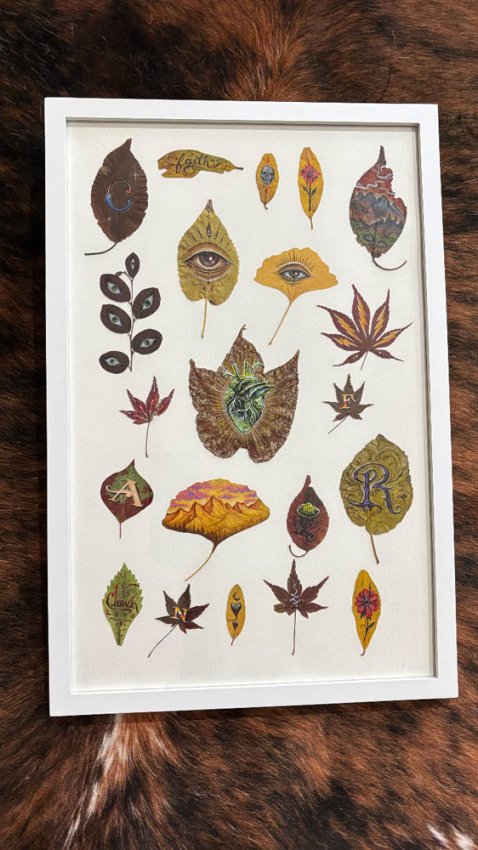

Art was always there too. An aunt who was constantly making things. Teachers who noticed he was always drawing. Family members who stepped in and said this matters and we should encourage it.

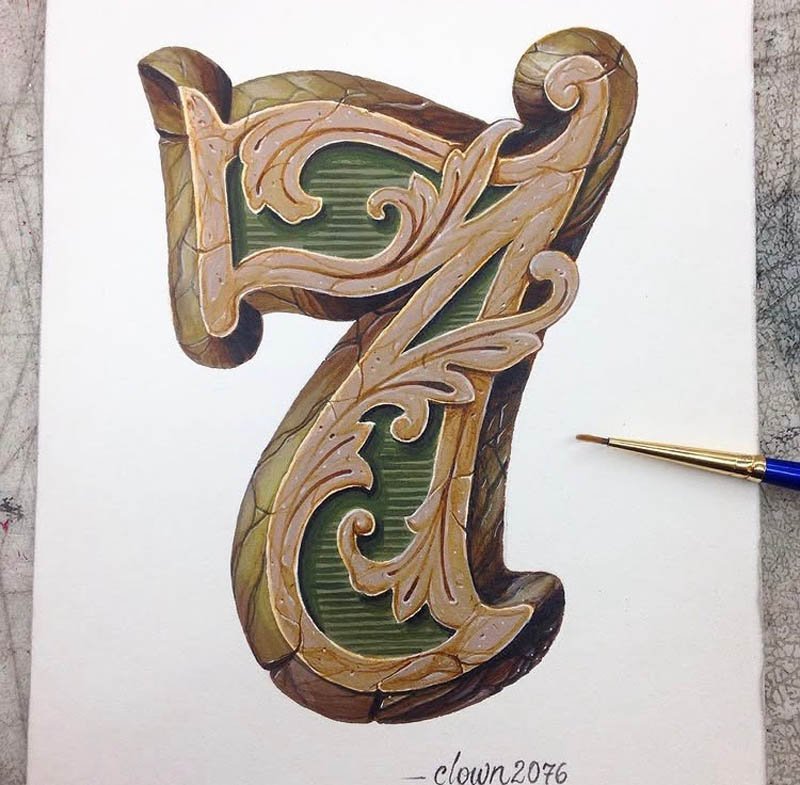

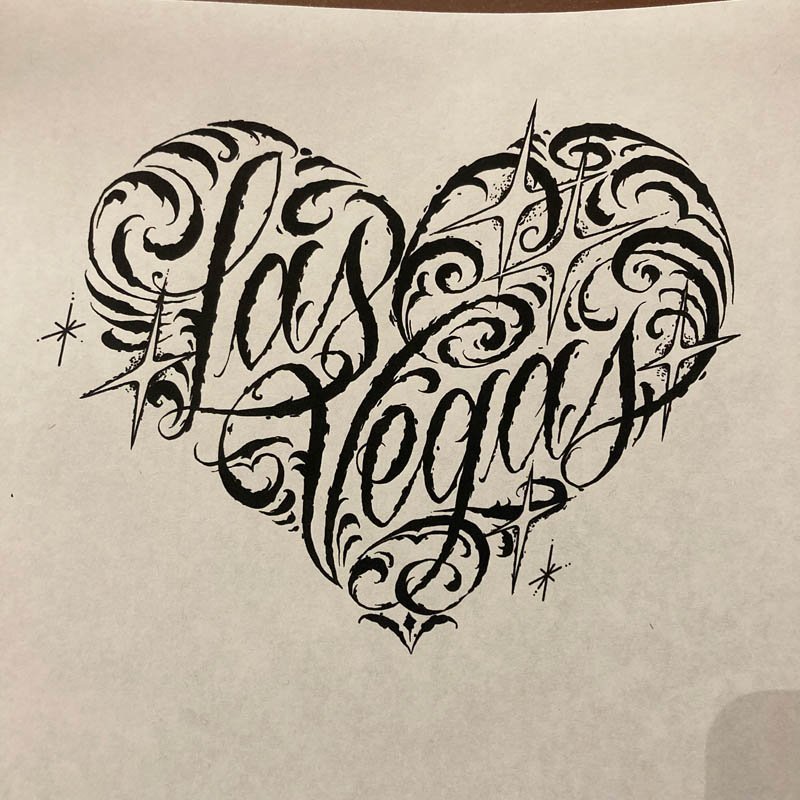

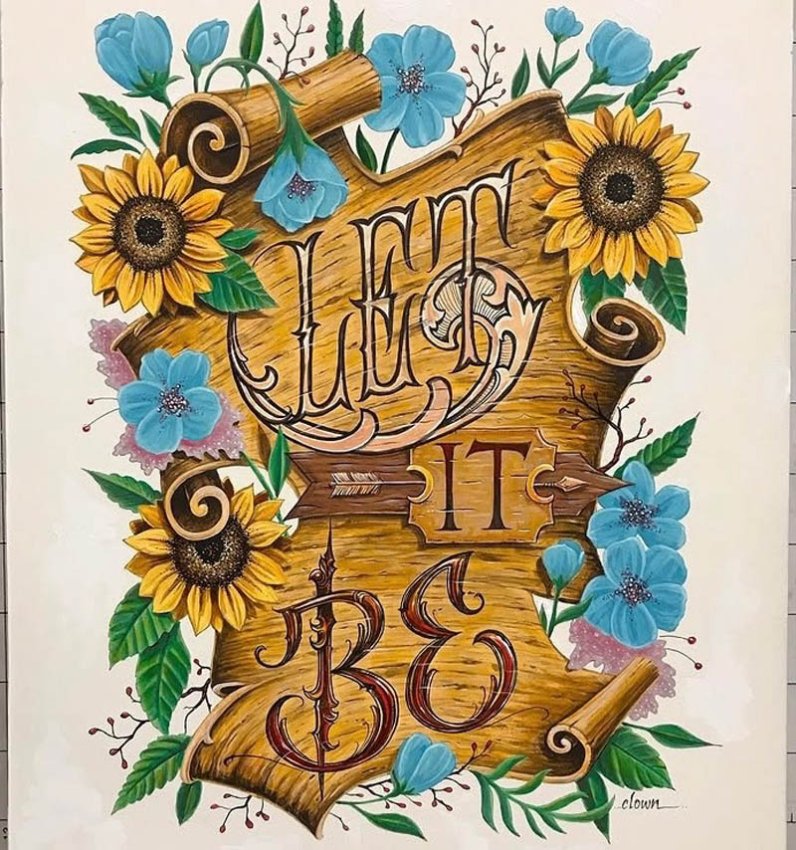

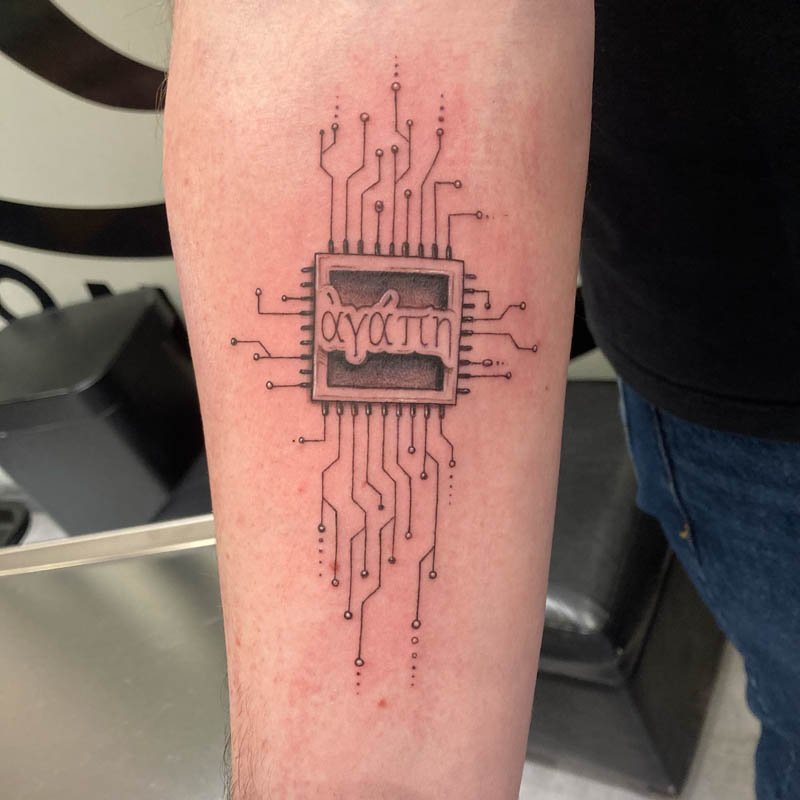

Artwork by H&H tattoo artist Matthew James Powell

“I was always drawing. Ninjas, Bruce Lee, stuff like that when I was young. Then skateboarding took over and I started drawing what I saw. Graphics, lettering, skateboard art. That’s just what I did.”

Tattooing wasn’t some forbidden world to Matthew. It was normal.

“My grandfather was covered. Navy guy. My dad had tattoos. There was never any stigma around it for me.”

Still, tattooing wasn’t the plan. For years, Matthew worked in Los Angeles painting sets and creating artwork for commercials. Big productions. Big pressure. At one point, he found himself living on a soundstage for weeks while working on what would become the first iPhone commercial.

“I was already there seven years. That was as high as I could go. I got the paycheck and thought… this is it? This is all there is?”

That moment pushed him out.

At 33 years old, Matthew went after a tattoo apprenticeship, not wide-eyed or romantic about it, but deliberate. He already knew what the job demanded.

“I’d seen friends go through apprenticeships. I knew what I had to do. I didn’t need someone telling me.”

His apprenticeship in Tarzana wasn’t traditional. There was no ego, no posturing. Matthew showed up first, stayed last, cleaned everything, painted constantly, and did the work.

“I just did painting after painting. Sailor Jerry books, fundamentals. They guided me here and there, but they didn’t have to hold my hand.”

Tattooing was the hardest art form he’d ever learned.

“With painting, you mess up, you paint over it. Tattooing, you get one shot. Pressure, depth, flow. Everything matters.”

That’s why Matthew is relentless about fundamentals.

“Learn American traditional first. That’s the foundation. Contrast. Clarity. If you don’t have that, tattoos don’t age well.”

Over the years, styles changed and Matthew changed with them. Fine line. Florals. Softer work. Tattoos that move with bodies instead of sitting on them.

Tattoo by H&H tattoo artist Matthew James Powell

“The people changed the style. It’s not just skulls and daggers anymore. Tattoos have to fit the person.”

He noticed it most with women.

“They think about how tattoos sit on their body. How they live with them. A guy just throws a skull on his arm and forgets about it.”

Matthew doesn’t lock himself into one style. He never has.

“I come from graffiti. You don’t get stuck doing one lettering style. Same with tattooing. You have to be fluid.”

What hasn’t changed is how seriously he takes every single tattoo.

“Before every tattoo, I take a deep breath. I tell myself this could be the last one I ever do.”

That mindset followed him to Las Vegas.

When Matthew and his wife decided to leave Los Angeles after the fires, Vegas wasn’t the obvious choice, especially with hundreds of tattoo shops already there. He expected to struggle. Maybe even stop tattooing altogether.

“I figured I’d have to work construction or painting again.”

Then Hart & Huntington called.

“I didn’t even know about the TV show. When I told my wife, she cried. She knew exactly what it meant.”

At H&H Las Vegas, Matthew found something different. A fast-paced shop. A sharp team. Clients from all over the world walking in excited, present, and ready.

“People are on vacation. They’re in a good mood. You feed off that energy.”

Eighteen years in, Matthew still approaches every tattoo the same way. Focused. Grounded. Fully committed.

“If I can surprise my coworkers, the people who see my work every day, that’s the goal.”

No hype. No shortcuts. Just the work.